THE FINDING OF ’SECRETS OF HELSINKI’

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

14.08.2012. Kamppi, Jätkäsaari. Helsinki

Helsinki is pretty ideal place for cycling. Today we are visiting a Helsinki based bicycle maker, Pelago. We meet early in the morning in the Pelago shop in Kalevankatu. Timo Hyppönen, the other half of the two brothers who found of Pelago some four years ago, shows us around.

–Here’s one of our basic model. This can serve now as a sample of our basic thinking behind the bikes. It’s a very simple model with as little breakable parts as possible. We aim to have it use still in 2050. It’s got galvanized fenders, rims and spokes in stainless steel, rost protected chain, light aluminium pedals, a leather saddle, and so on. And you can get the bike as single-speed, 3-speed or 8-speed.

–Then we got some lighter ones, like this new model ’Stavanger’. The frame in this one is designed here in Helsinki by my brother. This one is like a swiss knife; you can modify it to suit your needs by choosing from a variety accessories to different handlebars.

Company: Sorry for an amateurish question, but why do you need to have your own frame?

–The frame is like the heart of the bike. The essence. All things revolve around it. The frame holds all details to fit components on it. It’s very important for us to have our own frame to start with.

C: And that bike has a very unique frame. Do you sell this too?

– Yes and no. Not yet. The design for the production is still a bit in process. The frame of this bike we make in Finland. It would be great to be able to make more steel work here in Finland. We are also planning on making a bike for children. But maybe more about that later. It always takes a couple of years before a product is really ready.

Company: How many bikes do you yourself own?

–Hmm. Just two. I have no bike-fetish. Meaning I don’t collect them. And unfortunately I haven’t had much time myself to cycle around lately. But I do take into test use the new model we make. Looking forward to have some leisure time to ride with it.

C: How many people are you nowadays?

–Pelago has been nine people this summer. During winter there’s not so much work, so then we’re less.

We take a look into the bike repair studio behind the shop, and then walk to Jätkäsaari, where the assembly of Pelago bikes is done. The walk takes just 10 minutes from the shop (by bike that would be less than half the time but since Johan and Aamu have no bikes, we force Timo to walk his bike with us).

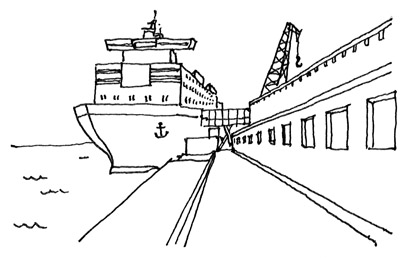

There’s a real industrial mood in Jätkäsaari, with its ship building docks and warehouses. In front of one of the houses stands a row of Pelago bikes. Timo adds his bike in the row, and we enter the building.

We meet Mikko and Aleksi who are assembling bikes in the vast space looking over Hietalahti. Steel racks holding bike frames stand on the floor waiting for Mikko and Aleksi to add the missing parts. The assembly is very craft oriented and needs no power tools.

C: Amazing space. And amazing view. You must like it here?

– Yes. We like it here. Unfortunately this building will be renovated in near future and we probably will not be able to afford the newly renovated prices. But it would be great to keep the production in this area. Anyway, we’d need less space than the ship building still existing on the opposite shore.

C: And is it important for you to be in Helsinki?

– Yes. I live here and got all my friends here. I want to have a biking distance to work, and to have the same for our workers. It’s great if one does not have to move following your workplace or travel great distances every day. Cycling is a logical and positive option compared to any other vehicle for urban traffic.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

23.05.2012. Vantaa, (almost in Helsinki)

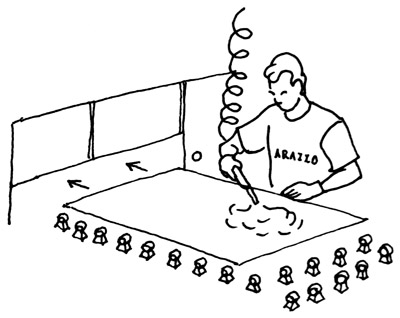

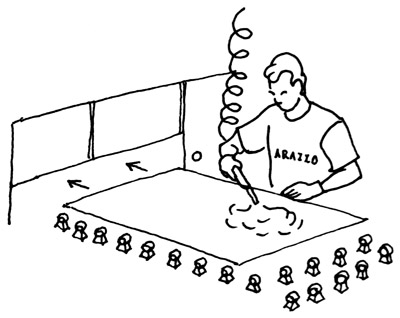

Today we are visiting Arazzo just outside the Helsinki city borders. We’ve got pieces of wool and silk fabric with us and a plan in our heads to print a scarf celebrating Helsinki. Arazzo mainly focus on printing fabrics for upholstery and curtains but handle also stickers, films, wood and aluminium plates, you name it. Nowadays they also print fabrics for dresses, lately a few that walked into the Presidents palace during independence day reception.

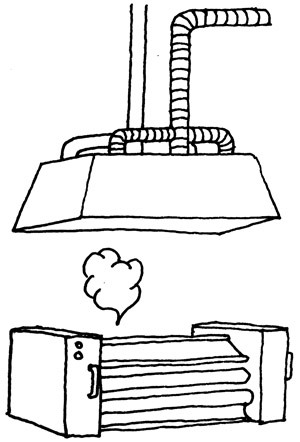

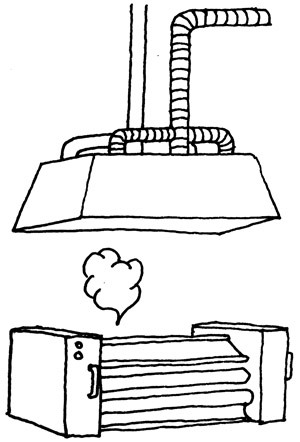

Teija Kuukkanen welcomes us and takes us to the production space. Huge printers under giant size air-condition units fill the space. These machines can print onto almost any flat material that can fit under the nosels of the printers. That would be up to 70 mm in thickness. Other dimension are quite impressive too; 3 meters in width and up to 6 meters long. With fabrics, the lenght is infinite.

We are happy with much less than that and show Teija the sample fabrics we brought.

–Should be no problem. We can do this with our inkjet machine for natural fiber fabrics. It sprays the ink straight onto the fabric and connects it with heat. Just send me the file and we’ll get you tests in a couple of weeks.

Oukidouki. We head back to office.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

07.05.2012. Vallila, Helsinki

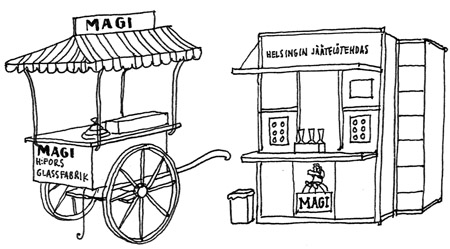

On a late Sunday evening Annette Magi from Helsinki Ice Cream Factory (Helsingin Jäätelötehdas) send us an sms: ’Weather forecast for next week looks good. We'll mix ice cream tomorrow morning. Welcome to see. Annette’.

On Monday morning we skip breakfast counting on getting some tasty samples on our visit to the factory. Helsinki Ice Cream Factory in Mäkelänkatu is the oldest, continuously operated, ice cream factory in Finland.

And how right we are! As we walk in, Annette Magi, who's grandfather started the company, hands us each an ice cream stick.

–These ice cream sticks have been in production for 50 years. Still grandparents buy them for their grandchildren, thus teaching them to be our loyal consumers, laughs Annette.

–There's four of us working here. Me, my sister and our husbands. And now my son is also helping out when the busy summer season is starting.

Ice cream making is indeed a very seasonal business. The factory mixes ice cream only if the weather forecast promises sunshine on the days that follow. Having the factory in central Helsinki means that delivery to the five kiosks that Helsinki Ice Cream Factory operates around Helsinki takes no more than 10 min. –And you can taste that, says Annette.

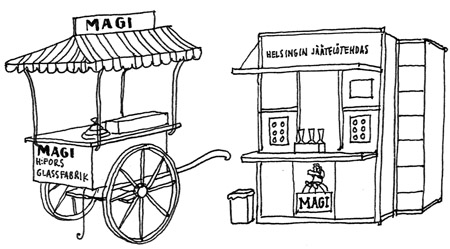

Earliest and latest versions of ice cream kiosks.

We put on white overalls, hair caps and shoe covers, and enter the production space.

Björn (Annette's sisters husband) and Annette's son are busy mixing the ice cream.

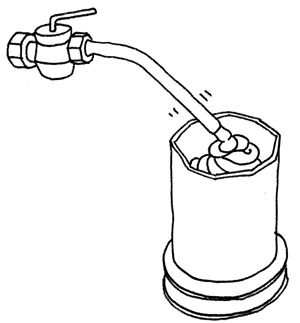

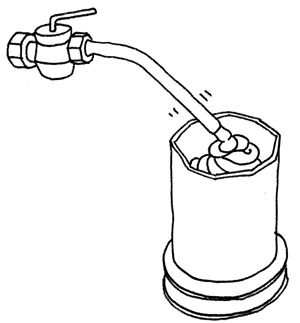

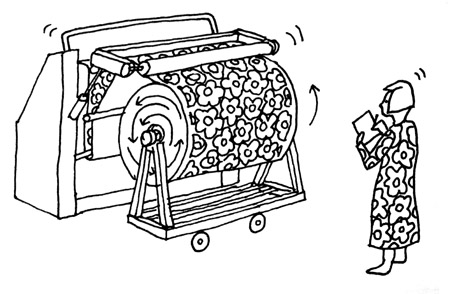

Two big drums filled with a mixture of butter, sugar and milk powder are humming in the vast space. Björn adds flavors into the drums and in a few minutes fresh ice cream starts gushing out. Annette's son is moving the filled barrels into the freezer room.

COMPANY: Impressive looking machines these. Do they have names?

Björn: I call these my first and second wife. I spend more time with them than my [third] wife.

Annette fills three small cups and hands fresh ice cream to us.

–If we could sell this, right the way it comes out of the drum, that would be just fantastic, says Annette.

The fresh ice cream is silky smooth, just cold enough not to be liquid. And insanely tasty!

–We produce some 90 000 liters of ice cream with these machines. 90% of that is made during the summer season, tells Annette.

COMPANY: Has the factory always been here in Mäkelänkatu?

Annette: My grandfather and his brothers started in 1922 in Keskuskatu, then moved to Eerikinkatu, to Liisankatu, and into this space in 1999.

COMPANY: Do you also live in Helsinki?

Annette: I do. In southern part of the city, where also our kiosks also are located. But I really can't enjoy walks in the parks there because then I see our kiosks and start to worry how the sales are going, and so on…

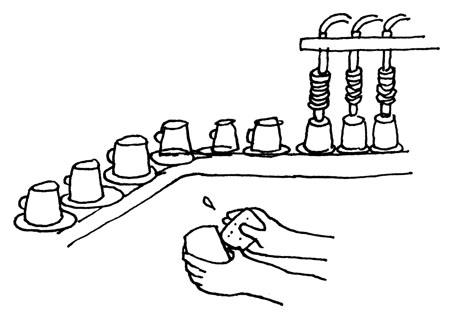

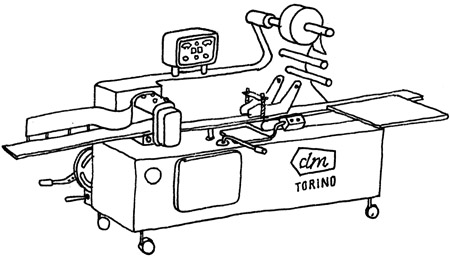

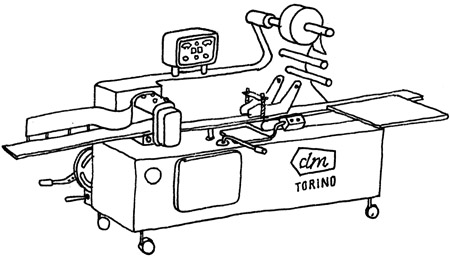

Ice cream stick wrapping machine.

We move to the next room where the containers are washed. A pressure washer and boiling water is used to keep the containers clean.

–People usually have this idea that working in an ice cream factory on hot summer days must be nice and cool. Nobody believes how hot it gets in an ice cream factory, laughs Annette.

COMPANY: Is it possible to design a custom flavor?

Annette: We carry 18 different flavors. Developing a new flavor takes a lot of trial and error, so we don't have a possibility to do customized flavors.

We return our overalls, say goodbye and head back to the office. On Tuesday we pay a visit to one of the Helsinki Ice Cream Factory kiosks in southern Helsinki. Tastes so good. This must be the ice cream we saw produced yesterday. So totally worth visiting.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

04.04 2012. Heikinlaakso, Helsinki

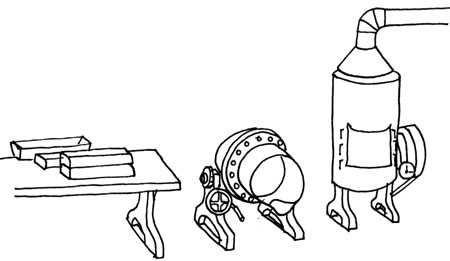

Today we pay a visit to Peltiveikot (the Tin Dudes) in Heikinlaakso.

The company was founded here in 1959 by two dudes both called Veikko – hence the name. Heikinlaakso is a home for quite a few companies working with steel, including Hellmanin konepaja, Kemell, Tasoteräs, Peltiveikot and more. And just a few hundred meters south from here is the area of Tattarisuo, which has even more work shops dealing with steel (we'll do a report about Tattarisuo later on).

Peltiveikot can make anything out of steel. Or of other metals. For instance copper. Some of Salakauppa's facade material is copper, bent and cut by Peltiveikot.

Ossi Pirnes welcomes us and takes us on a tour.

The Peltiveikot building is one large industrial space – clad in steel, of course.

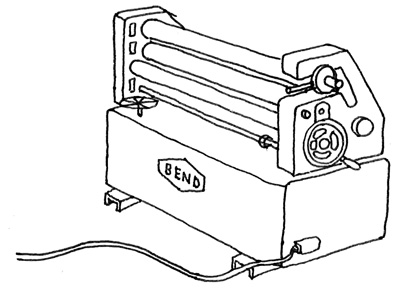

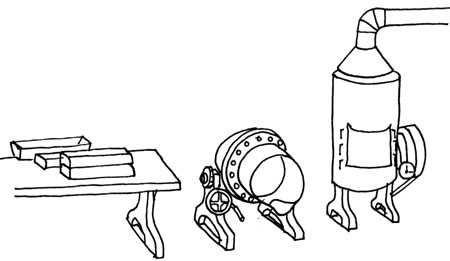

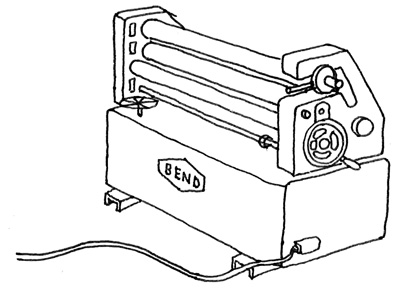

Inside it is filled with machines; rows of sheet rollers, lathes, milling cutters, pressers, welding machines and many kinds of polishing tools sit side by side along the walls.

Ossi demonstrates how some of the machines work. We test several polishing tools (here Ossi operates a sand blasting machine) on sheets of stainless steel.

The presentation is a bit fragmented since Ossi's cell phone keeps ringing each and every minute. That must mean good business.

COMPANY: Is it good for business to be in Helsinki?

Ossi: It's good, it's good. Most of the stuff we do stays inside Helsinki. So the clients are very close. Clients are mainly construction companies, planners, factories, cities and municipalities…

COMPANY: Do you do all the production here in Heikinlaakso?

We have some spaces in Vantaa, where we work with ’black steel’ (FE). And we work with many sub-contrators, for paint work, CNC cutting, galvanizing. They're all mostly here in in Helsinki. We don't have to go further than Järvenpää to find everything necessary.

COMPANY: And are you from Helsinki?

Ossi: I'm from Vaasa. But I've been here in Helsinki for decades.

We won't steel more of Ossi's time and so we head back to the office to start planning what we could do together.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

03.04.2012. Kallio, Helsinki

Today we'll meet the ceramists of Dragonia in Kallio, Helsinki.

The walk to their studio will be a short one. 25 steps to be precise. Since we are both located in the same building.

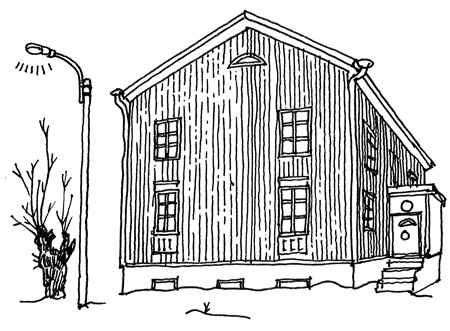

First, a few words about this house in Kalliolanrinne 4. It's an industrial building built in the 30's and 40's and nowadays hosts a mix of things. The basement has band studios. The first, second and third floor are occupied by a print house, a ceramic studio (Dragonia), two wood workshops, a fashion designer, an upholstere, and a stone mason. The floors from three to six are filled with artists, designers and architecture offices. The attic has ghosts – seriously.

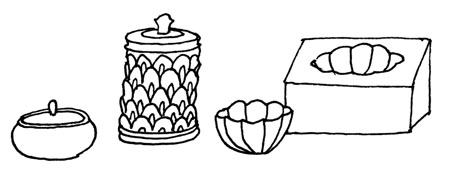

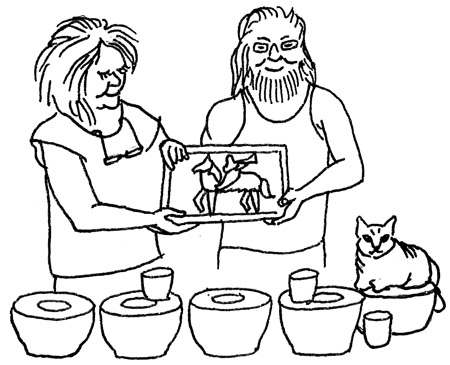

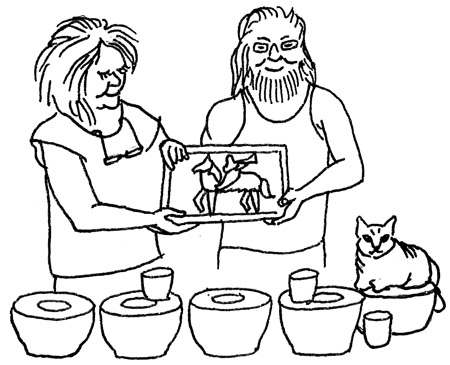

Back on the second floor, where Dragonia has been since 2009, we are welcomed by Kirsi and Petteri, and their cat. Dragonia has been producing limited series of tableware for restaurants, cafés and the souvenir market, since 1999. For years, Dragonia has been selling their products in the Kauppatori outdoor market.

Petteri: There's a heavy competition with ceramics produced in large quantities far away, but we believe in locally made crafts. We focus on small souvenir products. We've kept on shrinking the size of our plates because the tourists flying to Helsinki need to travel light.

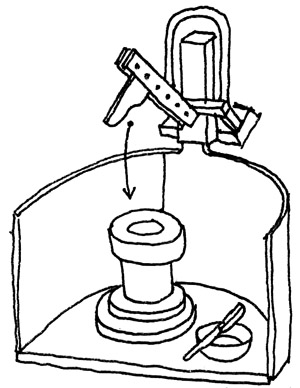

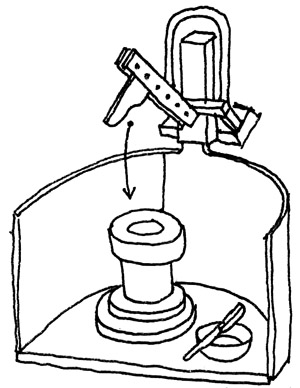

The shelves are filled with ’basic moulds’ of plaster that are used to shape for the plates and cups. The clay is placed inside a mould of the forming machine, which turns the shape quickly.

The German clay used in this technique is quite solid, facilitating the forming process, says Petteri and adds: ’Like the German's, the clay is dry’.

It is then time for the decorative imprints: Dragonia's speciality.

With this technique, custom made series can be produced relatively easily.

One very fine looking decorative pattern titled ’midnight sun’ is created using the cork from a sparkling wine bottle.

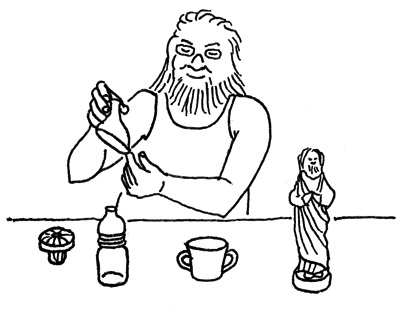

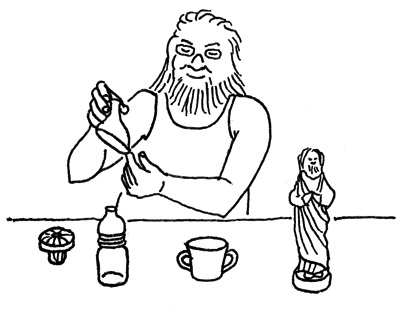

Kirsti shows more of the collection of found objects she uses in making moulds for casting ceramics. Shapes from PET bottles and plastic containers become parts of new ceramic items.

Kirsti has used even broccoli when creating a knob for a casserole dish.

I had to do that cast very, very quickly – before the broccoli melted, says Kirsi.

After forming – or casting – the shape, the pieces are glazed.

Kirsi does the mixing and spraying of the glaze herself. It's by trial and error only to find the right mixture, explains Kirsi. After years of experimenting Kirsi knows what the right mixture needs, and all of the Dragonia products carry a certification. In the corner stands a kiln where the glazed pieces will spend the next day and a half.

We've been traveling from Kuopio to Rovaniemi, from Busan to Wakken to meet manufacturers for the last five years, but never knew that our closest neighbor is one of them.

We say goodbye and walk the 25 steps back to our office.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

22.03.2012. Kauniste. Toukola, Helsinki

The basement of this beautiful wooden house in Toukola is where Kauniste linen towels are printed. The classic Kauniste print is a mixture of old printing techniques and young illustrators.

We are welcomed by Hiro, one half of Kauniste, and Chewie (yes, as in Chewbacca from Star Wars), not the other half of Kauniste but Hiro's and Milla's hairy pet from Spain.

Followed by Chewie, we move inside to the printing room where Hiro gives us a demo of the printing process. He looks like a top chef from a TV program when he mixes the colors. All colors are mixed by hand, using only gut feeling to estimate the amounts of pigments needed.

Hiro places linen tea towels on the print table and transfers the print onto the fabric with a single stroke. The alignment for additional layers of color is done by hand, and so every print becomes unique. Johan also gets to try printing, and, by pressing the spatula way too hard, manages to leave an ever lasting imprint on the table. Sorry… Hiro places linen tea towels on the print table and transfers the print onto the fabric with a single stroke. The alignment for additional layers of color is done by hand, and so every print becomes unique. Johan also gets to try printing, and, by pressing the spatula way too hard, manages to leave an ever lasting imprint on the table. Sorry…

Hiro takes us further along the three room factory.

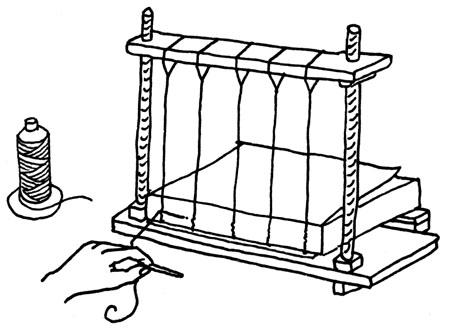

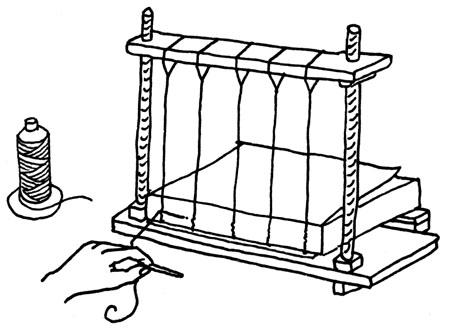

Everything is made from scratch here. The whole process starts with Hiro building the print screen frames. Then illustrations are transferred onto the screens. There's a tiny cave-like darkroom where this is done. It's evident Hiro's got some real engineering skills when he demonstrates how all light can be shut with very original curtain systems and the fluorescent lights tubes lit.

The demo is interrupted by Milla (the other half of Kauniste) who arrives with fresh pulla, and so we take a coffee break. The demo is interrupted by Milla (the other half of Kauniste) who arrives with fresh pulla, and so we take a coffee break.

Milla is explaining that Kauniste got started when Hiro met Matti Pikkujämsä, a Helsinki based illustrator. After learning that Matti is a well known illustrator, the idea of their own print factory combining illustrations with traditional screen printing grew in Hiro's head. And so, soon after, Matti's first illustration ’Sienet’ was printed. Nowadays Kauniste works with several young Scandinavian illustrators and has built a very impressive, and a recognizable, Kauniste collection.

The Kauniste collection include aprons, bags and cushion covers but linen/cotton tea towels are really the main product of Kauniste. Milla and Hiro can print up to four hundred tea towels per day. After printing, the fabrics are hung out to dry. Then all is left is the ironing, folding, packing, and finally shipping, of the fabrics. Kauniste has resellers both in Finland and abroad, mainly in Japan and in Northern America.

We say goodbye and head to the office to think how we could contribute to the beautiful collection of Kauniste prints.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

07.02.2012. Ullanlinna, Helsinki

|

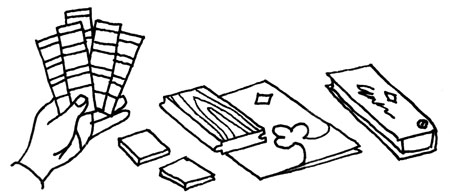

here probably aren't many master book binders left in the whole world, but one happens to be right here in the heart of Helsinki, in Tarkk'ampujankatu. The place we are visiting today is Kirjansitomo (Book bindery) V. & K. Jokinen, called ’Lafka‘, founded in 1928, and it is in this very same building they've been ever since. |

We are welcomed by Toivo (Topi) Salo and Vesa Jokinen, who's great grand father founded this company. Topi and Vesa will enlighten some of the secrets behind book binding for us.

– We do a lot of conservation and restoration of old books and we have kept our manufacturing means old as well. Most of the techniques we use are hundreds of years old. Everything is old here. Even those wall papers over there are the original ones, says Vesa.

The production spaces indeed look more like an apartment – as they were designed, and also used for during and after the war time. We start our tour from the ’hall’. Here Topi is repairing old books. The work is very time taking and requires a lot of patience. This is fine with Topi, because he anyway wants to take his time to admire the print work and paper quality of the old books.

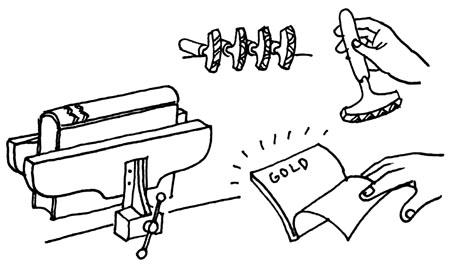

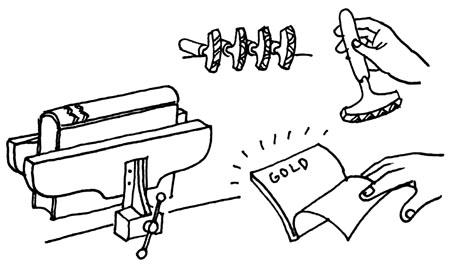

We continue to the living room where book covers are finished. The walls are covered with drawers containing brass letters and ornaments. On the corner table stands a press used to decorate book covers – which is done using real gold. The brass ornaments are heated and rubber in gold leaf sheets and then pressed on the covers to create the decorations. This work also requires a lot of patience and time. Topi shows us an old history book with golden ornament all over its leather covers.

–This must have taken a full week of work for a skilled master, says Topi.

Next room used to be the sleeping chamber (makuukammari) where now the binding of books takes place. Publishing houses and the university library send volumes of magazines to be bound together here. A pile of a full year of daily newspaper is quite an impressive sight. The only modern device here is an industrial sewing machine that can be used in connecting newspaper's sheets before they are bound together by hand.

The kitchen is where the cover materials are stored. Rolls of ’kluutti’ (a paper/cotton book cover fabric) are stacked high up on the walls. ’Kluutti’ is the most common of the materials used in book covers. – We do make covers also out of leather; goat, veal, board, artificial leather… even fish skin – if the client brings their own material. One of the most odd cases was a man who wanted his book covers to be made out of his own leather jacket. We did that, but basically we don't make special, one-off pieces here – that area we leave for the art book makers, explains Topi.

COMPANY: What is the most popular article people bring to you for binding?

Vesa: (Laughing) Must be the Donald Duck volumes. One business man brings his Duckburg Tales every spring to be bound in leather covers – so that he can read them on his summer vacation. Repairing a family bible is also a common task we get. Families want to restore their bibles before handing them down to next generation. But mostly it's binding thesis works for graduating students, making guest books and addresses and so on.

C: What's the biggest book you've made?

Topi: The exact measurements I don't remember… but it took two of us to carry it out of here. We also made the guest book for Santa Claus, which is one of the biggest books around.

C: Oh yes it is! We have seen that one in Santa Claus home in Rovaniemi.

C: When did you start book binding?

Topi: 1952. In Porvoo. Ten years later I moved here (to Helsinki) to study gold plating in the Ateneum school. It was actually Vesa's great grand father, who opened the door for me when I first rang that door bell. And here I am still. It's been 50 years now.

C: And how does one become a book binder?

Vesa: There's a school in Sastamala, Finland. There you can start. But it's by following the old tradition, been an apprentice, how you learn this profession. We have one apprentice at the moment. That makes us eight people working here nowadays. And we hope Topi is still going to continue for some years.

Topi: I will. This is fun work. Often I forget to go home – before my wife calls and reminds me.

C: Your location is quite impressive. How is it to be in central Helsinki?

Vesa: It's very nice to be so close to the city center. Most of our clients, especially university students, find us easily. They can reach us by foot in few minutes. Our clients do the logistics mainly themselves, so we don't have to worry with the traffic and the narrow one-way streets around here. This is a sort of work that doesn't require a lot of space. That's why we haven't seen the need to move into bigger spaces and out of the city.

Topi jumps on a table and reaches for a high pile of books. He returns with a beautifully bound book covered in leather and burlap – the history of ‘Lafka’ V. & K. Jokinen, written by Vesa's father Olavi Jokinen. The cover is both designed and manufactured by Topi Salo, a master book binder.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

23.01.2012. Herttoniemi, Helsinki.

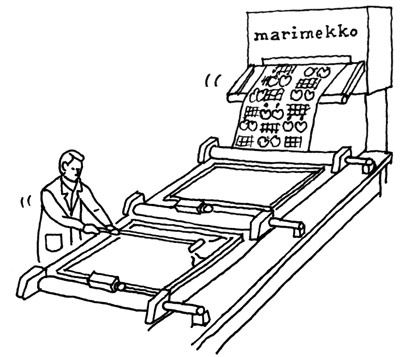

Today we are visiting the Marimekko-house, Marimekko’s headquarters and textile printing factory in Herttoniemi, eastern Helsinki. Marimekko is a Finnish textile and clothing design company. They are known all around the world for their original prints and colors. Alongside prints, Marimekko also designs and manufactures clothing, interior decoration textiles, bags and other accessories.

Maarit Heikkilä from company’s marketing communications greets us in Marimekkos's new canteen, just opened today. We take some time choosing a coffee cup since they all come in different Marimekko prints. Equipped with hot coffee we head for the printing facilities.

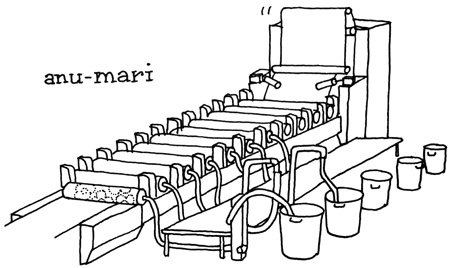

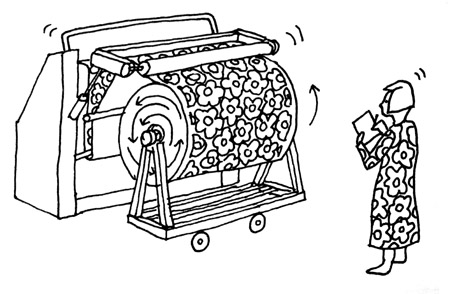

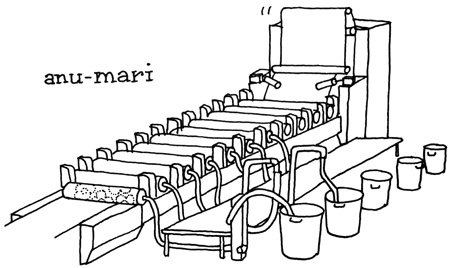

The production spaces have just been cleaned and colourful Marimekko fabrics are shining against a clean, grey background. We meet the production manager, Anu-Mari Salmi, who shows us the latest of the print machines – also named Anu-Mari... after Anu-Mari, of course.

This brand new rotation printing machine (came online in October 2011) prints a seamless pattern and enables Marimekko to triple the production capacity. In 2011, the printing factory produced 1.45 million metres of fabric.

The colors used for printing are all mixed here. The ready colors are fed into the machines 12 rotating cylinders, all with perforated surfaces transferring the colour onto the fabric. The printed fabric is then fed into steam machine that attaches the colors. Finally fabric is washed (in 95°C), dried, finished and rolled to next room where quality control is made. No machine has yet replaced the human eye as the best tool for the quality control.

Anu-Mari tells us she usually jokes to visitors that the quality controllers also have to count the amount of flowers in the patterns.

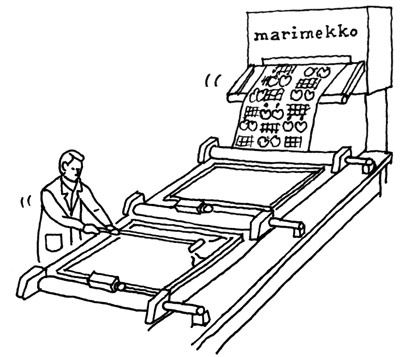

We pay a visit also to the more traditional flat printing machine. Here the patterns are transferred onto print screens using a fairly similar exposure technique as in silk screening. Each screen prints one colour. This forty meter long machine has 12 screens – which is the maximum amount of colours used for one design.

Anu-Mari lists the benefits of being in Helsinki. –Logistics run very smoothly. We've got the harbour around the corned and the airport just 20 minutes away. Helsinki Water provides us with all the water we need. Also Marimekko was founded in Helsinki and it would feel unnatural to be located elsewhere. We do have other production elsewhere in Finland. Our bags are made in Sulkava and purses and jersey garments in Kitee.

We continue our tour to the design and prototype making spaces. Designers run around dressed in Marimekko.

–It's not obligatory to wear Marimekko clothing here, laughs Maarit. –But most of us do that anyway. And of course our homes are all draped in Marimekko.

We pass by the room of clothing design team and come across Noora Niinikoski, the Head of Fashion Design of Marimekko. Noora tells us she's currently living in the spring of 2013. The new collections are designed well in advance, usually a year or two ahead.

Next space is the showroom where new fabrics are displayed. There are patterns from designers with long history with Marimekko but each new collection includes also prints from new, upcoming designers. A new stationary collection is also about to be launched in autumn 2012. Armi Ratia, the founder of Marimekko in 1951, was herself a passionate writer.

We say goodbye to Maarit and head for some shopping in the Marimekko premium and outlet stores downstairs.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

15.11.2011 Tikkurila, Vantaa (ent. Helsingin maalaiskunta).

Today we are crossing the Helsinki city borders for a visit to Tikkurila paint factory – in Tikkurila. This area used to belong to ’Helsingin maalaiskunta’ but is nowadays part of the city of Vantaa. Tikkurila factory started here before the city existed. Founded in 1862, there was pretty much nothing else around here.

On the way to meet Riitta Eskelinen, the Brand Manager of Tikkurila, we are passing by the ‘test field’ where different paints are tested in real life conditions. Rows and rows of stands with painted samples stand facing south (heaviest sun) in 45° angles (exposed to rain). Time tells how paints withstand the weather conditions.

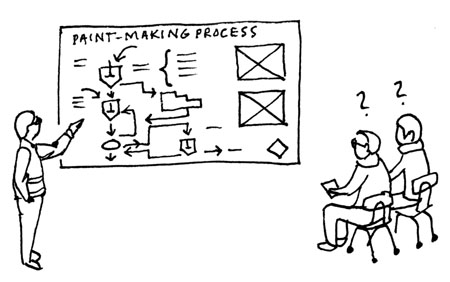

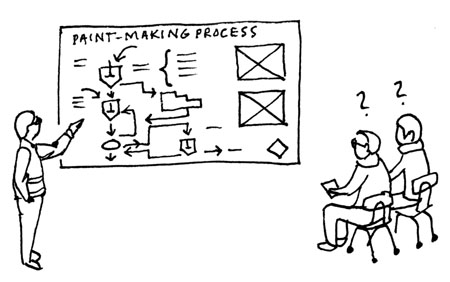

Riitta takes us straight to the paint factory to meet Samu Hörkkä, Production Manager. In here, some 60 million liters of paint is produced every year. Paint making is a fairly simple chemical process, says Samu, showing us a very complex looking sheet of data. Seeing our confused faces, Samu tries again and explains that mixing paint is like mixing ingredients in the kitchen, just using very big kitchen blenders. And as in ice-cream business, paint making is a very seasonal business. It is the summer time when things get really busy. Then here is 850 people working with some 50 trucks moving in and out every day.

We are handed safety goggles and switch off cell phones when entering the plant.

All containers are painted in bright orange or in bright green, depending whether they contain water based liquids (green) or solvent based (orange) liquids. There are huge pigment silos hanging from the ceiling. This was a new idea by German engineers who designed the plant in 1975. The silos hanging high up means only gravity is needed to feed the pigments to the mixing units. The whole is a closed process, so we don't get to see the actual mixing of the paint.

We continue to the warehouse which has 18,000 pallets of paint cans stacked in the shelves. That's 6.5 million liters of paint and is quite an impressive sight. The big warehouse makes it possible to deliver any kind of paint for a customer – on a following day after the order is placed. The ideology of Tikkurila is based on tinting (mixing the final colour) which is done in the shops by the retailers.

COMPANY: We're curious to know how long does a paint stay good? COMPANY: We're curious to know how long does a paint stay good?

Samu: The pot life is officially 5 years but a solvent based paint stays good basically forever.

We pass by a filtering unit and some huge sci-fi looking robot arms waving about doing what they are supposed to do. One conveyor belt carrying paint cans travels through a small hole in the wall. Samu explains that it's made that way in case of fire; the small opening can be closed quickly. The fire is the thing one has to take seriously when using big amounts of solvents. Everywhere in the ceiling are sprinklers and the plant has got its own fire brigade – and Samu is one of the firefighters, ready for action when needed.

Samu: We rehearse here twice a month.

COMPANY: Wow! That's so hot! Do you have fire men uniforms and a pole to slide down and all that?

Samu: Not a pole to slide down. But uniforms yes. We can get to any location in the factory area in less than three minutes.

COMPANY: What is your favourite paint?

Samu: Tikkurila Vinha. It's an outdoor paint. One of the most important feature in paint is how easy it is to repaint the surface. Removing old, bad paint is what takes time. Applying new paint is fast. Vinha has a very good quality with this. Miranol is one of our classic paint that I like also. Nowadays it says ‘furniture paint’ in the can because of EU regulations, but basically you can paint almost anything with it.

COMPANY: And the most hated paint?

Riitta: Well, not exactly a paint but a shade. It's the ’Painters White’ (maalarin valkoinen) which is nothing but a bright white dirtied with some black. We have many nice alternatives like the brilliant-white paint ‘Lumi’ (snow) but it's difficult to change customers’ belief in the professional sounding ‘Painters White’.

COMPANY: Is it good to be in Tikkurila?

Samu: Logistically it is one of the best places. This is really the cross-roads of Finland.

COMPANY: A favourite colour?

Riitta (laughing): I always wear black. I never use colours myself, I just market them to other people. For exterior painting, we see it as our responsibility to offer colours that are in harmony with the Finnish tradition.

Here is our colour card for wooden houses. As you can see, there's a lot of ‘punamulta’ (barn paint) variations in here. On the other hand, we offer trend colours, ideas and inspiration for interior decoration.

We collect a bagful of colour cards and brochures, say goodbye and head back to Helsinki.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

17.11.2011. Pitäjänmäki, Helsinki.

This is going to be one delicious day. Because we'll be visiting a candy factory! Here in Helsinki!

Halva candy factory started in the Helsinki city center, in an old milk store in Meritullinkatu, Kruunuhaka. In 1940's the company moved, into an even more central location, to the Sederholm house in Aleksanterinkatu, which is the oldest stone building in Helsinki. The 40's was tough time for candy making because of the lack of sugar. In the fifties candy making continued and a new product – liqourice – was introduced. A new factory was opened then in Pitäjänmäki, and here the production continues today.

The name Halva by the way comes from halva – that classic sweet and dense confection – which is still hand made here.

In Pitäjänmäki, we are greeted by a man in white, Ilkka Rissanen, the production chief, who'll show us around the factory today.

Company: Hello. How is it like to work in every kids dream job – a candy factory boss?

Ilkka: It's much like working in any other food industry. Quite physical work.

Company: What's your favorite candy?

Ilkka: Soft liquorice.

That's our main business. Liquorice is made by mixing suryp, molasses, liquorice powder, sugar, anis and wheat flour. We export roughly half of our production. Mainly to the Nordic countries, and to U.S, Spain, Australia. For the Fins we make also salmiakki-lakritsi, liquorice with ammonium chloride. And for the Swedes we make red strawberry liquorice. We also do ’kosher’ candies to Israel. A rabbi from there comes here once in a while to observe the manufacturing.

C: Is liquorice good for you?

I: At least it speeds up your digestion (laughing). Liquorice has been noted to have several positive effectives on health. Effective against ulcers, cough, infections, etc…

C: Is it good to be in Helsinki?

I: Yes it is. It means very short distances to main storages (keskusvarastot/kesko) and also that we can deliver straight to many of our big customers here. And our staff can come and go easily. Downside is the traffic. You have to think about timing and try to avoid rush hours in logistics.

The Halva company is a family company. It was started by a man named Jean Karavakyros, and is nowadays run by a man named Jean Karavakyros. And it is not the same man, since the company is celebrating its 80 year birthday this year.

But now we finally go to see the candy factory. We are dressed in white gowns with a red logo embroidered on the pocket. The hat with a cotton ball like candy texture on our heads makes us feel like proud pro candy men. Now the big door opens and a warm, sweet breeze enters our noses.

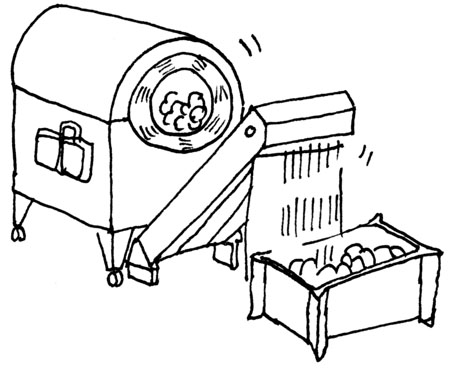

Aah! This is amazing! The strips of liquorice are 50 meters in length here! The ovens that could fit a van inside are filled with candies! There's a huge polishing machine here! For loose candies! It's really hard-core industrial meininki this candy making.

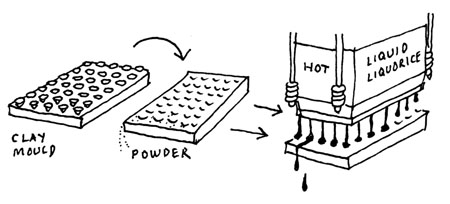

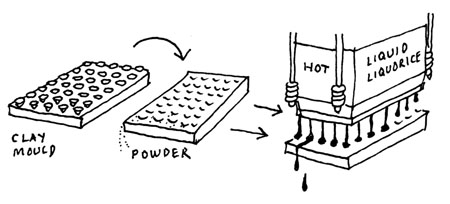

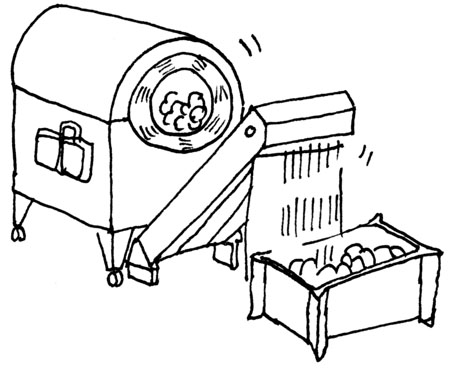

The fifth and fourth floors are where moulded candies (valumakeiset) and marmalade are made. The moulding of the candy is quite a delicious process. The mould used is a frame filled with plaster candies. This is pressed on a similar wooden frame filled with flour. The imprints of the flour frame are then filled with hot, liquid candy. The filled frames are put to oven to get rid of extra moist. Then the frames are emptied into the polishing drums which filters away the flour (it is recycled for next set of candies) and polishes the candies. Polishing (with added oil) is needed to keep the candies loose inside the candy bags. The casting moulding machine, which looks much like an off-set printing machine, does the first three steps of the process automatically.

In third floor is the sweetest machine ever. This is where the liquorice strips (lakumatto) are made.

Hot liquorice is injected into strips that run on a wide conveyor belt towards an cooling unit. After cooling, the strips are run over each other and cut in short pieces. The cut pieces drop to another conveyor belt wrapping them into their packages. This 50 meter long machine runs non-stop night and day for five days a week.

We continue downstairs and pass by the production line for halva. This sweet is hand-made using a few old machines that look like they're from the Wizard of Oz.

Ilkka shows us a very small room under the staircase between the first and second floor. Aahhh. This room is filled with plaster candy moulds with shapes of small bears, big bears, feets, hands, rabbits, shoes, mobile phones of '90s, mobile phones of 2000, faces of king kong, coins, old cars, new cars, fishes, birds and more and more. This is the mini museum of halva loose candy (irtokarkki)!

In the first floor is the candy factory ’outlet’. The shop has a selection of all the goods Halva is making. When we shake hands for a goodbye, Ilkka hands of huge sample bag of the best of Halva candies.

In the back of the house (which smells delicious unlike most factory back yards) is a pipe protruding from the wall. Next to it is painted the word ’siirappi’ (suryp). This where the tank trucks, bringing 25 000 liters of suryp at time, connect their hose and pump the goods into the building.

We're writing this report very high on sugar after eating our souvenir package we got from Ilkka. Too bad there are no more candy factories left in Helsinki that we could visit for more.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

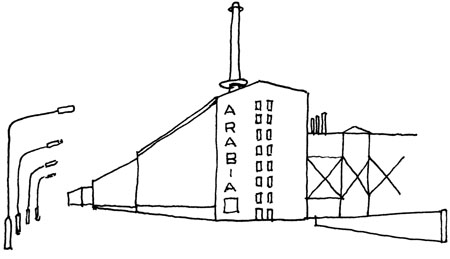

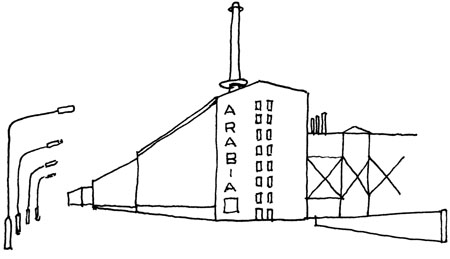

04.11.2011. Arabia, Helsinki.

Today we are visiting the Arabia factory in Arabia, Helsinki.

The production started here already in 1874. Nowadays Arabia belongs to Fiskars Group, the oldest company in Finland. Quite an impressive history in this historical building almost in the middle of Helsinki.

Taina Grönqvist is taking us to top floor where the Arabia museum, gallery and the Arabia Art Department are located. The Arabia Art Department, consisting of ceramic artist working independently in their studios, have been here since its founding in 1930's. All is bright and white. Both due to big windows letting the sun shine in and because of the white ceramic dust covering all surfaces.

We take the elevator to the bottom floor where the factory is located.

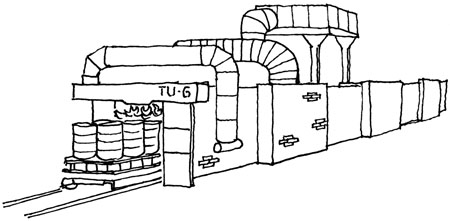

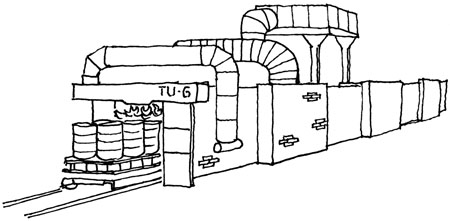

Everything is huge in here! The ovens stretch over 80 meters in length, taking the ceramics for a 19 hour cruise through the oven. The oven looks like a mini scale hell which would swallow and then burn all faulty and dirt. Or like a giant size sauna that has a holy spirit with authority.

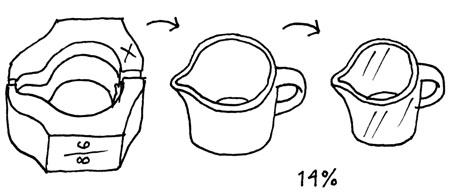

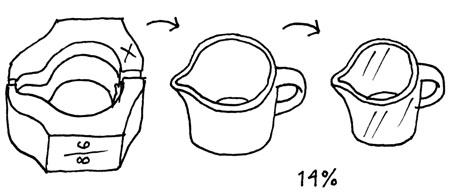

It takes a full week to cool down these ovens when the summer holidays starts here. The oven shrinks the ceramic by 14% and so all the moulds are made that much larger.

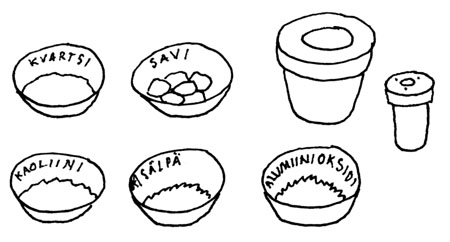

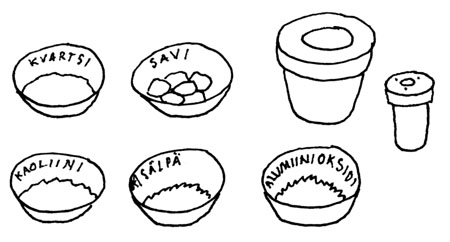

Let's take a few step back to see how the manufacturing process starts. A display table is showing the ingredients and tools used in making ceramics. The raw material is stone, quarts, clay and kaolinite, all crushed and mixed together before pressing them into the moulds.

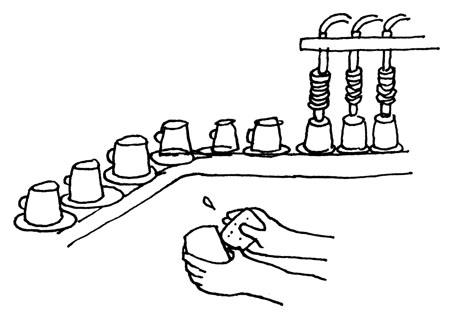

The pressed mugs and plates move around in conveyor belts where they are examined and trimmed by hand. After trimming they continue to glazing machine and are piled in trolleys taking them to the oven. Glazing is what Arabia is really mastering. The Kilta series designed by Kaj Frank from the 40's was the first of a kind where an even colored glazing was needed, and the glazing has ever since been the Arabia's field of mastery. There is approximately 60 different steps in making a Kilta (nowadays called Teema) cup. Behind simplicity lies a complex process.

There's a beautiful bell ringing sound when we pass the quality control department. When the ready cups are examined they are gentle banged together to find errors which the eye cannot see. The sound will tell to an experienced ear if there is something hiding underneath a smooth surface.

One of the factory column is like a massive tree covered with ceramic tiles that transforms the atmosphere from the factory into fairy factory tale. Many corners of the factory are decorated in style of each nationality working in the factory; the decoration department here looks like a small shrine.

There's approx 150 workers nowadays working in the factory. It's divided in two departments; the ’factory side’ and the Pro Arte side. Pro Arte is where products requiring skilled craft are made.

Karri in Pro Arte department is very exited; when recently modifying the spaces to fit a new air conditioning system, they accidentally bumped into a hidden storage containing old moulds designed by old masters in early 20th century.

First of these findings are now put in re-production. This collection feels very fresh yet classic with a secret story behind.

We say goodbye to Taina and head for some shopping in the factory outlet after this impressive factory visit.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

01.11.2011. Hernesaari Helsinki.

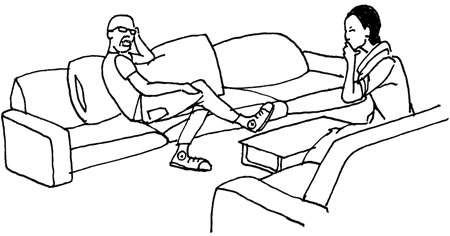

Today we meet Hokke Långstedt for an interview at SAAS (a LED and fiber optic lighting company – see earlier report 01.06.2011) and talk about Helsinki, manufacturing, underground, sauna, and – of course – the Swedes.

While Johan prepares to record the interview, Hokke grabs a remote control and adjusts the ambience – both the music and the lights. From a steaming hot red light into ice cold blue, we finally settle for a dim, neutral light.

Johan: Ok. Recording. You used to actually use the label ’Made in Helsinki’ in your products?

Hokke: Yes we did… And I don't know why we actually stopped it. Because I am extremely proud of my city. Or not proud – I love it.

There is something special about Helsinki. I can't really put my finger on it. I've been working a lot in Stockholm, so I compare the two cities quite a lot. And I love Stockholm too. But when I define the two cities, I think that in Stockholm are the marketing people and in Helsinki are the artists.

J: Yes!!!

Hahahaha

H: It's the roughness I love about Helsinki. Like around here the ship yard buildings. The ’isot koneet’. I love that. Industrial. And I think Helsinki has, during the past ten years, developed a lot. But it's the people who make the city. We are little bit rough, little artistic.

Hahahaha

A: And simple.

H: And simple, yes. Which suites me. We have a lot of Swedes coming to visit here. We go and have a sauna in Harjuntori.

A: You go to Harjuntori with Swedes?

H: Yes. And they love it! Somebody should show you the city, it's heart. It's becomes a completely different city. From the fact that you are just a tourist coming with the ferry and go to Kauppatori and… then you go back.

That was the Helsinki where you live in. Then there's the Helsinki where you produce things. And local companies like Amak are vital for us. During the past we've learned each others way of operating. I can make quite rough sketches and they know what I want. And how I want it finished. I'll show you this (reaches for an heavy looking aluminum thing). … This is something we made. 105 water fountains with lights for a spa.

A: Where?

H: Close to Saimaa, Lappeenranta. A holiday club. This is metal work by Amak.

A: Beautiful!

H: And they did all 105 pieces without any prototyping. We had all the parts, printed circuits, different sort of nosels that you can have different sort sprays and rgb lights – and you can control each of these. They are just really, really well made. Even if you don't know what to use it for, you'd want to have it. Just because it's such a nice piece.

Hahaha

J: A high-tech weight lift maybe.

H: The thing is that we are near each other. That's also why we have our own papa (workshop) here. When customers visit here, we can test things. It is vital that you are very near the process.

A: Joo. I believed some 5 years ago in telephone and emailing but not anymore. Real face to face meeting and the feeling that we are near is quite important.

H: And I think you can actually see that in the quality.

A: Could you guess why this making culture is disappearing in the capital area, in main cities? Or why is it hiding?

H: I think you need to do something specie to survive here. You cannot produce the same stuff that everybody else is doing. Obviously, if we are manufacturing things five minute walk from Stockmann, our costs are higher than if we would be somewhere in the woods. We need to be a bit more innovative. We cannot just make ordinary lamps in here. They would be just too expensive and nobody would buy them. If we do something which people are willing to pay a little bit more, then we can do it here. And we do stuff where it is important to be near the customer.

A: If we for example visit a factory in, let's say Mikkeli, the product is somehow ’Mikkeliläinen’. And if we go to Jämsä, the product is very much ’Jämsäläinen’. Do you see Saas has a Helsinki spirit?

H: Yes I do. What I want SAAS to be is ’High Class – Underground’.

J: Mmmm.

H: I love if we can be surprising. That people are surprised in a positive way. Of course there are people who are surprised in a negative way. But that's ok. You don't need to apply to everybody. But it's nice if you get a reaction. The worst is if people are indifferent of what you are doing. Then it's not worth doing.

In away the underground, subculture, is disappearing. The world is changing so much that when someone does something somewhere in the world you know about it the next day. Already a hundred thousand people know about it. But one sort of luxury for people is to discover things for themselves. They found it, and it becomes theirs. And so you do it in your way. Even if you do it all over the world, you do it in your way, in a local way.

Quite often we try to do something that competes at with the Italians, the Swedes – of course – the Danes, what ever. And we of course cannot compete with the Italians, I mean, they've got mass industry and so on. We have to do it in our way. And we have to be ready to also accept that everybody doesn't get it. And that's completely fine. We will always have a little bit less money, always have a little less this and that and so on…

A: Hahahahah. So correct.

H: It's so silly then – when you have only three people and a thousand euros – and then you try compete with someone who has fifty people and millions euros. You have to do it in a different way. I think there's a bit of a culture of that in Helsinki. You can see it in… like Flow festival started in a back yard somewhere in Uudenmaankatu some years ago – and now it's a venue of, what, eighty thousand people. But still they have the same feeling in it. And ok, it might happen that it becomes too big or too something, but then something else happens again. But they still have kept the feeling of the original, of what it was all about. Just a couple of friends who put on a good party. And from there it started.

J: Maybe that's the good thing about Finland. It's not actually possible for things to grow too big. They always stay interesting, marginal.

Hahahahaha

H: Yes. But then in the same hand I'm totally impressed and a big fan of what the Angry Birds are doing all over the world. But they are still doing it with a bit of an attitude. It's maybe not a typical Finnish attitude but it's an attitude. The whole concept of an attitude might be one of the most important things one can have. In almost anything that you do. Especially if you are running a company. The company should have an attitude towards things. And that should show. Even if it's quite difficult to define, you should get to all of your people, and to people you are working with.

A: Is dark winter helping lighting business?

H: It is. And I love it. I love dark.

Hahaha

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

25.10.2011. Pakila, Helsinki.

Sokeain ystävät (The Friends Association of Blinds Finland) factory is located in Pakila, Helsinki. We meet Simo Parviainen from Annansilmät-Aitta who has kindly agreed to show us around. There is approximately 15 people with different kinds of visual impairments working in here.

Simo takes us first to meet Anita and Galina who make teddy bears, toys, decorations, just about anything out of fabric. Their studio is filled from floor to ceiling with rolls of fabric. In the middle is a big table where Anita has a teddy bear in her hands. This bear can move her head and all of its limbs. She is made in a very traditional technique and is filled with wood chips.

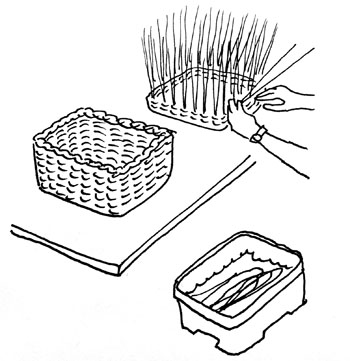

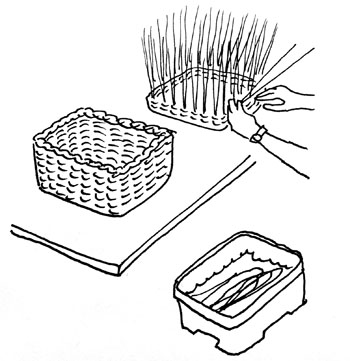

We continue to meet Margitta who works with rattan. She is soaking the rattan strips in water before braiding them into baskets, trays and flower stands. The rattan comes from Indonesia. It is only sold to Federations for Visually Impaired outside Indonesia. Sometimes Margitta mixed it with Finnish willow to make the baskets sturdier.

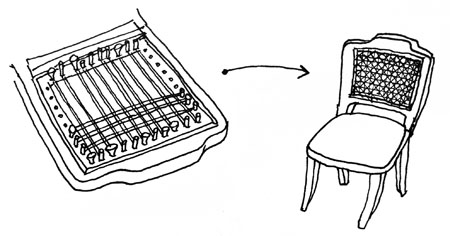

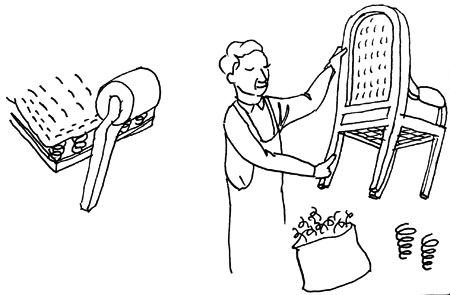

Markku Varasa works next door to Margitta. He's also braiding rattan here but his business is all about furniture. The frames come ready bent from Ostrobothnia, Finland before Markku starts his braiding work. Markku is also restoring broken rattan braiding of old furniture and also making brooms in his studio. The most commonly used material in the most common brush (katuluuta) is made from a tree bark that grows in Sierra Leone.

Arto in next studo is happy to show us just how fast he is in making pot brushes. He quickly ties a bunch of rice roots in a bundle and tosses it along with others waiting for the trimming of the ends. Arto has been making all kinds of brushes for almost twenty years.

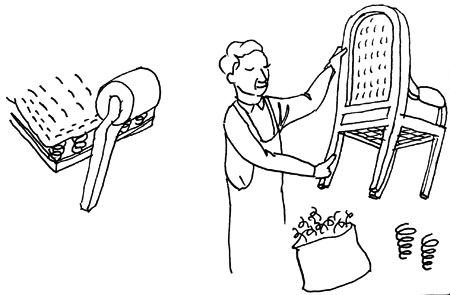

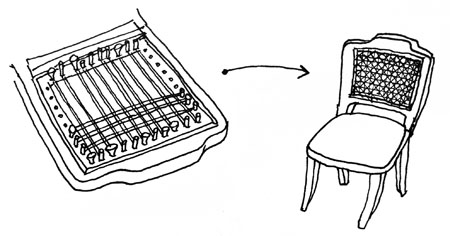

Last along the corridor is a studio restoring antique furniture. Tuomo and Jorma are applying here old techniques to old furnitures. Binding springs with layers of seaweed, excelsior and burlap, the craftsmanship looks almost too beautiful – before it's all hidden under the upholstery fabric. Tuomo has been restoring furniture for a venerable 38 years.

The Friends Association of Blinds Finland are renting these spaces for the visually impaired entrepreneurs. Everyone here has their own businesses and work straight with clients but also produce items for the Annasilmä shop that Simo runs. Each seems to have their own speciality and their own studio space to work in. This factory feels like a dream factory where everybody does what they like best.

|

![]()

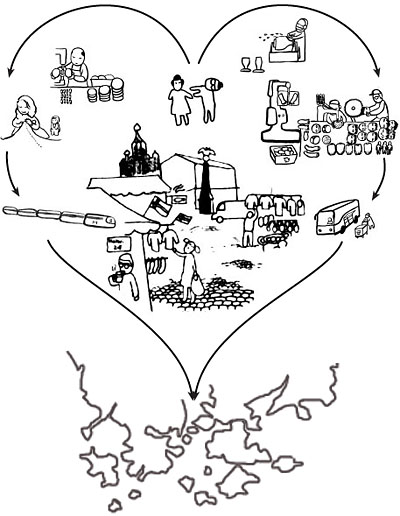

Helsinki Scarf / Helsingin Huivi

Helsinki Scarf / Helsingin Huivi

COMPANY: We're curious to know how long does a paint stay good?

COMPANY: We're curious to know how long does a paint stay good?